Everyday Materials, Extraordinary Care

Mirna is a second-year Product and Industrial Design student whose work begins at home. Her design philosophy took a decisive turn in 2024 when she realised she did not want to create for aesthetics alone, but for the everyday needs of her parents. From apps to architectural prototypes, her practice is less about objects and more about connection, restoring dignity, nurturing belonging, and reminding her family, and by extension her community, of home.

Favourite Space

For Mirna, her favourite space is not one location but two that overlap. The first is the prayer mat: a place for one-to-one conversations with Allah, where clarity emerges in a world that rarely pauses. The second is home with her family, where she shares everyday moments, listens, and learns. One gives her direction; the other translates love and care into action. Together, they shape how she sees belonging.

Design as Devotion

For Mirna, design is an act of care. She treats every project like a seed something that needs patience, room to breathe, and freedom to grow rather than control. When the process becomes overwhelming, she returns to empathy: stepping into the shoes of the person she is designing for, asking, “Would this truly make their life easier?” If the answer is no, the design is refined until it does. For her, devotion lies in that quiet act of service.

A Personal Lens: Home, Food, Language

For Mirna, belonging has always felt elusive. “I don’t fully belong to the UK, and I don’t fully belong to Iraq,” she reflects. “Sometimes I even wonder where my parents belong.” In these gaps, design has become her bridge — a way to honour her parents’ journeys, to restore fragments of home, and to root herself in the in-between.

Her first turning point came at the end of her first year studying product and industrial design. Tired of abstract briefs, she looked closer to home to her mother. “I realised I could design something useful if I focused on her,” she says. The result was an app that used AI and real-time feedback to help her mother practice speaking English more confidently. “That was when I realised design could be more than theory. It could shift confidence, build connections.”

For Mirna, belonging comes down to three words: home, food, and language. If you hold these, you belong. In prayer, too, she finds a sense of grounding: “Praying is like a one-to-one with Allah reflection, distraction fading away, feeling zen.” And in her mother’s arms, she adds simply, “That’s home.”

Spaces & Beyond: Atmosphere as Memory

One of Mirna’s most moving projects began not in a studio, but with a sound: the Adhan project. While visiting Bosnia, she recorded the call to prayer echoing from the mosques and sent it to her father, who could not travel. His response sparked an idea.

“Late at night, I thought I wanted to build a mosque for my dad,” she recalls. With cardboard models, laser cutting, and the help of a friend, she created a small mosque structure embedded with a Raspberry Pi and speaker that would play the adhan at its exact times.

She remembers the moment she revealed it to her father: the nerves, the waiting, and finally his childlike smile as the adhan filled the room. “The adhan brought him back to Iraq. Nostalgia, memory, belonging — it was all there. That’s when I knew it worked.”

For Mirna, design is never abstract. It lives in sound, light, and texture in the choreography of presence. “It’s about being intentional, making the connection, and putting in the effort to be present.”

Practices: Reflection and Empathy

Mirna’s design rhythm is shaped by reflection, zooming in and zooming out, always asking: Who am I creating for?

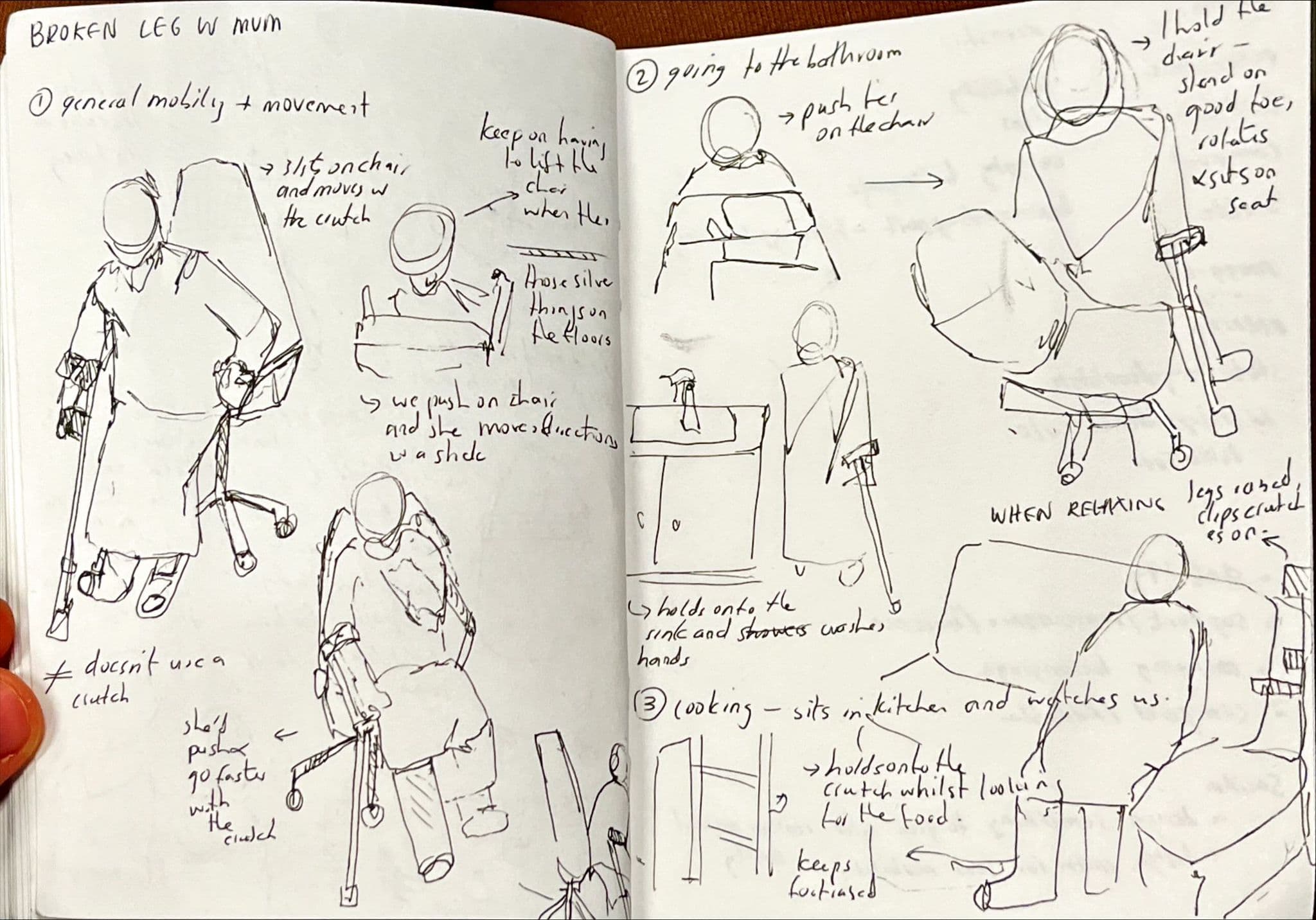

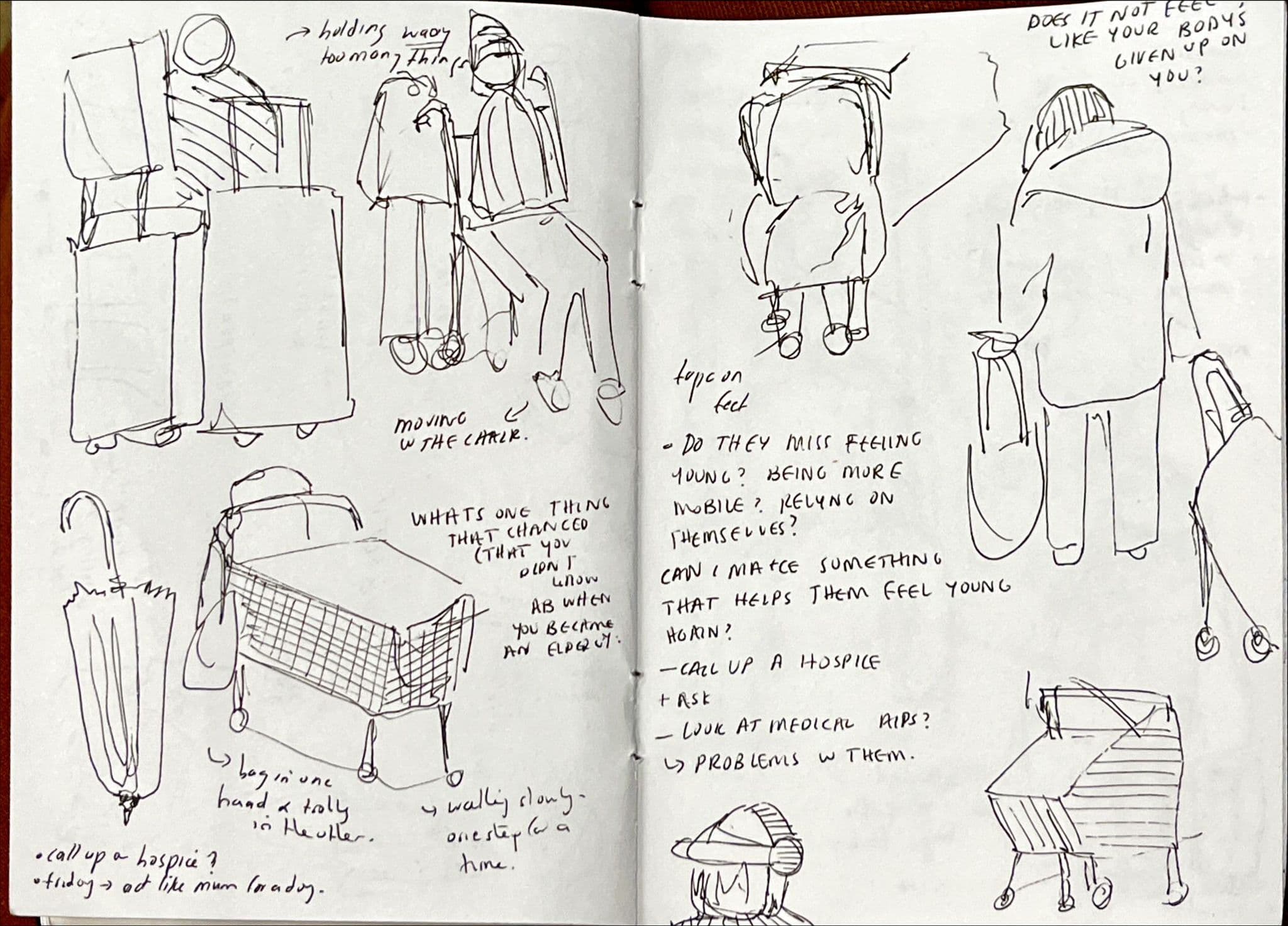

Her process is immersive and emotional. Silence, sketching, speaking with her parents. “They form the project and bring it together,” she says. She gives each project weeks, sometimes months of reflection: revisiting, storytelling, and recording thoughts on video.

Every project begins with empathy. When she was tasked at university with designing a mobility aid, she thought of her father, who had suffered a stroke. To understand, she spent a day using a wheelchair and crutches herself. “You need to put yourself in other people’s shoes — literally. That changes how you design and create products to serve your audience.”

Ramadan offers her a seasonal anchor. “It strips things back; there are no distractions, no music, just food, community, and clarity.” In summer, she walks and observes. In winter, she embraces the rain. “Every season becomes a studio,” she reflects, “and the season itself, a muse.”

Materials & Methods: The Everyday

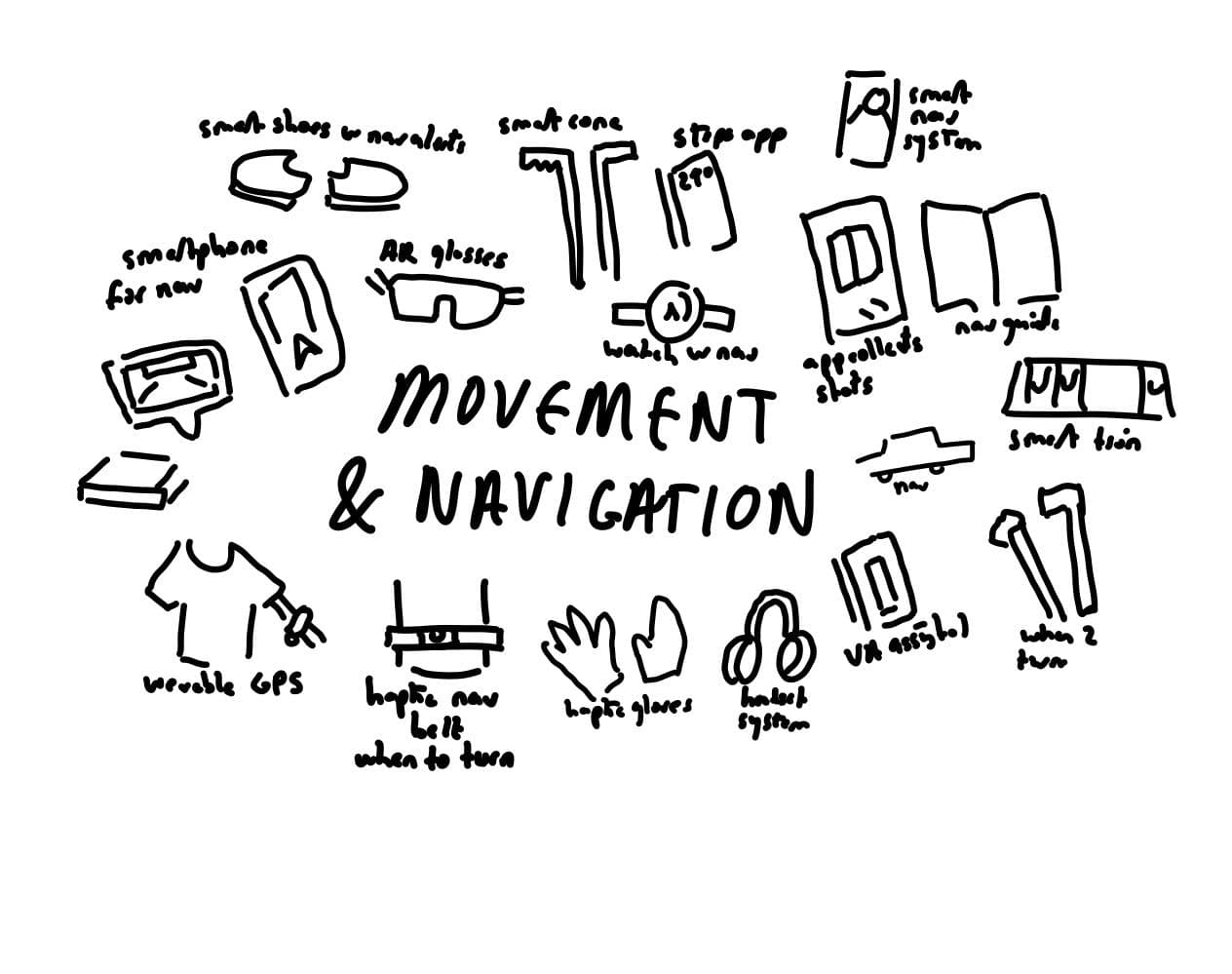

Mirna is drawn to everyday materials: cardboard, paper, pencils. “Everything starts with sketches,” she insists. Digital tools like Figma or Apple Pencil come later, but “using your hand is always first.”

Her memories of drawing with her mother infuse deeply into her practice. “She taught me cartoons and colours. It’s an emotional connection.” Her sketchbook, a simple Muji notebook, is never far, often tucked under her pillow like something sacred, ready to be used when inspiration strikes at night.

Principles: Thoughts as Trust

Mirna describes her philosophy as empathic, intentional, and open-minded. She draws on values of amanah (trust), ihsan (excellence), and consultation. At its core is a belief:

“If you thought of something, Allah gave you that thought. You’re the only one who can execute it.”

Her projects honour both heritage and innovation. Using her father’s favourite Iraqi reciter for the Adhan project, she wove nostalgia into code, memory into material. “It’s about learning from parents’ experiences and creating something new out of them.”

Signals: Designing for Connection

Mirna’s work carries a simple but radical message: you can create something from nothing. With no coding background, she built an app; with no training in electronics, she prototyped a speaking dome. “Design isn’t about being a professional. It’s about caring enough to try.”

Looking ahead, she dreams of breaking down barriers literal and figurative. One idea on her notes list: a live translation tool that removes the language barrier in conversations, allowing Arabic and English speakers to connect instantly. “If you strip that barrier away, everyone can connect.”

Her vision for Muslim spaces echoes this: mosques that are more communal, inclusive, and imaginative. “I hope my work inspires connections between people, not just Muslims, but anyone. Especially in mosques, we should create spaces for creativity and intergenerational learning. Our parents’ skills are treasures, we can’t lose them.”

On the Horizon: Imagination as Necessity

From building an app for her mother to crafting a mosque-in-miniature for her father, Mirna’s work is guided not by markets or metrics but by devotion to family, to faith, to the possibility of design as service.

There’s a tenderness to her process, a kind of soft futurism. Whether sketching a tool to help her parents navigate unfamiliar systems or prototyping with materials that remind them of home, Mirna approaches design as something sacred, lived, not displayed.

Imagination, for her, isn’t a luxury. It’s a form of remembering but a way of shaping space so that belonging isn’t just a word, but a feeling.